The Crisis of Vanishing Farmland

What’s at Stake for New Farmers and How We Can Save Our Agricultural Future

Having spent several years pouring over real estate listings in search of my own forever farm, I have become painfully aware of the cost of farmland. Farmland prices are rising and good land for farming is becoming increasingly scarce. This has serious implications for the future of the nation’s farm economy and farm system, but also for America’s agricultural landscape. As the older generation of farmers begins to wane, what will happen to their farmland? How will new farmers access land to grow the food that feeds our country? And, how can we preserve farmland for future generations?

Welcome to the Runamuk Acres’ farm-blog! If you are new here, I invite you to check out my About page to learn what this is, who I am and why I am doing this. Or just dive right in! At “Runamuk Acres” you’ll find the recantings of one lady-farmer and tree-hugging activist from the western mountains of Maine. #foodieswanted

Barriers to Farming

According to a 2009 report from the USDA’s Economic Research Service, beginning farmers face 2 primary obstacles:

High start-up costs

Lack of available land for purchase/rent

The study also found that beginning farmers tend to earn less income from their farms. They have more off-farm income and are less likely to rent farmland than established farmers. This is because rental agreements are inherently less secure than land-ownership, discouraging investment on the part of the farmer.

A 2011 report on beginning farmers “Building a Future with Farmers” by the National Young Farmers’ Coalition came up with similar results: 78% of respondants rated lack of capital as the biggest obstacle. 68% cited finding affordable land to purchase or landowners willing to make long-term agreements. 40% reported access to credit, including small operating loans.

Respondants found these barriers to be more challenging than business planning or marketing skills, finding good education and training.

The researchers from the National Young Farmers’ Coalition interviewed representatives from 30 different organizations around the country who work with farmers and found that the one issue raised by virtually everyone was access to land. The representatives interviewed pointed to many resources to help with financing and credit, farm production, and business and marketing skills, but few actual resources exist to help new farmers gain access to land.

Note: For more on the challenges beginning farmers face, check out this article from Choices magazine.

Rising Farmland Prices

Studies show that most farmers acquire land by purchasing from a non-relative. Therefore, trends in the farmland market are critical to entry opportunities and the cost of farmland. This explains why beginning farmers are more likely to not own land.

Between 2017 and 2022 farmland values have doubled in the United States. Those values are still rising today, driven by foreign investors and development pressures.

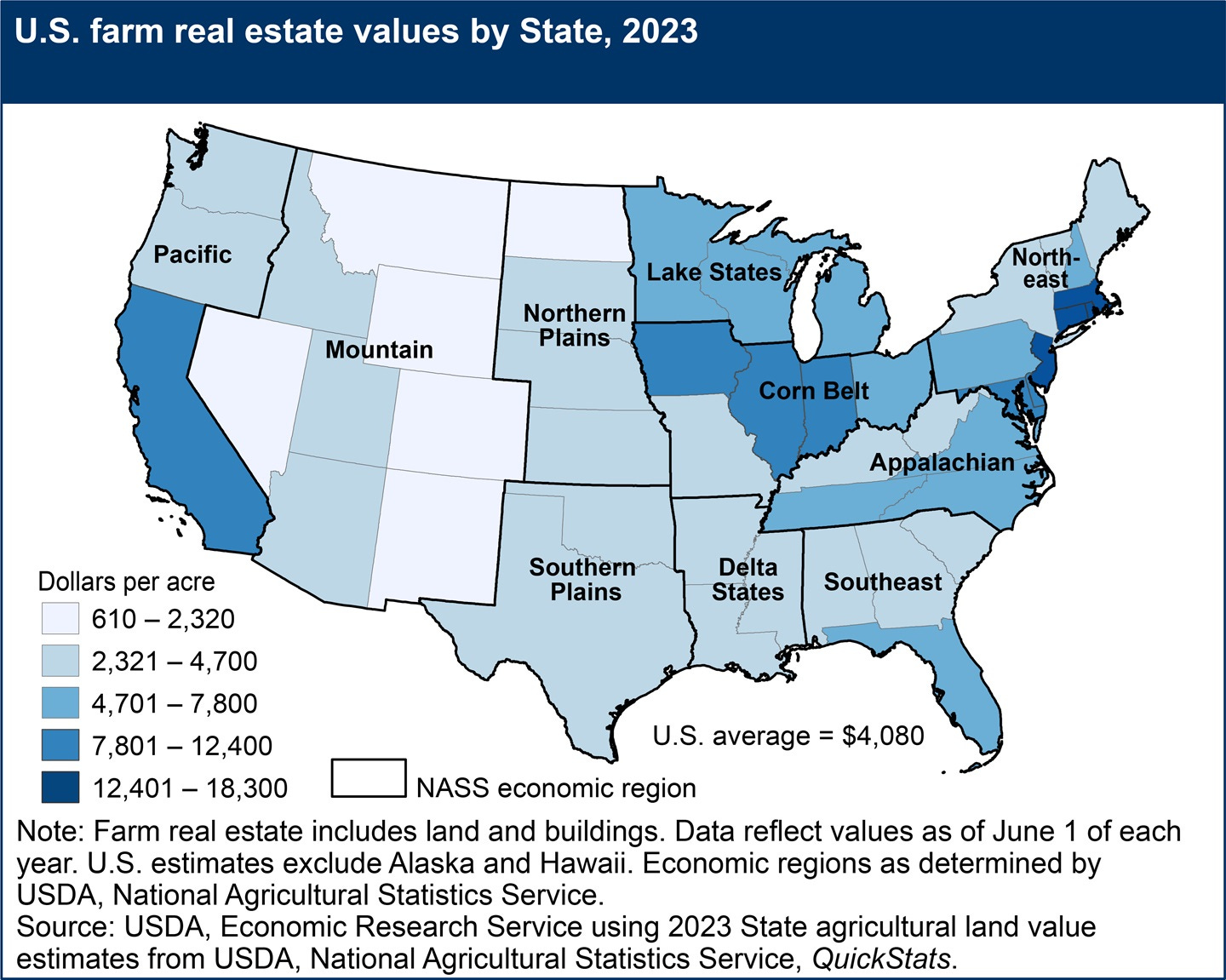

According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, the current national average is $4,080 per acre. But the agricultural value of land is dependent upon the quality of it’s soil─not it’s development possibilities─and how much income it can produce for farmers.

From the USDA Economic Research Service on Farmland Values:

“Farm real estate (land and structures) accounted for 3.18 trillion dollars (82.8 percent) of the total value of U.S. farm assets in 2022. Following a period of stabilization in farmland values from 2014 to 2020, farmland values began to appreciate in 2021, a trend which has continued into 2023. The USDA Economic Research Service studies trends in farmland values, assessing the impact of both macroeconomic factors (such as interest rates and the prices of alternative investments) and parcel specific attributes (such as soil quality, government payments, rural amenity value and urban proximity). The value of U.S. farmland averaged $4,080 per acre, an increase of 7.4 percent over 2022 values, or 3.9 percent when adjusted for inflation. Over the previous five-year period (from 2017 to 2022), the compound annualized growth rate (CAGR) was 4.6 percent, or 1.2 percent after adjusting for 3.3 percent inflation.1”

Due to historical program eligibility conditions, land used for cash grains such as soybean, corn, and rice, are more likely to have an agricultural base than other types of farmland uses (vegetables, fruit, nuts, livestock, etc.). Owning farmland with a base encourages established farmers to continue farming.

The ERS reports that since 2009, US farmland values have been supported by earnings fueled by record high commodity prices. When coupled with historically low interest rates, the market is able to support higher land values. This is a boon for those exiting the industry, but just the opposite for those trying to buy in.

Lost Farmland

In the 1800’s Maine had 6.5 million acres of open farmland. Everybody farmed then. Maine was such a vast state with homesteads so spread out across the country side that residents had no choice but to grow their own food. Since then a total of 1.3 million (or 22.4%) acres of land once dedicated to the cultivation of food has either been lost to the Maine woods or to development.

The phenomenon has accelerated in recent years. Economists detail how much more valuable that farmland would be if it were rezoned for development. Large tracts of land are being bought up and broken into smaller lots for housing. This has a serious impact on the farming industry, leaving beginning farmers fewer options when it comes to finding farmland. It also makes securing that land much more difficult.

Additionally, the farmland retirement program, the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), encourages established farmers with interest in retiring to place their land in the CRP, rather than exiting farming and selling or renting their land to other producers.

Economists detail how much more valuable that farmland would be if it were rezoned for development. Large tracts of land are being bought up and broken into smaller lots for housing. This has a serious impact on the farming industry, leaving beginning farmers fewer options when it comes to finding farmland.

Fewer New Farmers

Farmers between the ages of 65 and 74 represent the fastest growing sector of the farming population. According to the USDA’s 2012 Agricultural Census the average age of principal farm operators is 58.3 years old. There are twice as many farmers who are 75 and older, as there are farmers who are 34 and younger.

There can be no doubt that we need the new generation of farmers who are eager to participate in the local food movement. Yet between 1982 and 2007, the percentage of principal operators with fewer than 10 years’ experience dropped from 38% to 26%. The percentage of young farmers fell also, from 16% to 5%, with data from the 2012 Census confirming the continuation of that downward trend. Principal operators with fewer than 10 years’ experience now accounts for 22% of the total, while young farmers represent less than 6%.

The decline of beginning farmers and ranchers has been so sharp that in 2010 US Secretary of Agriculture, Tom Vilsack urged Congress to consider adding a policy goal of 100,000 new farmers.

Addressing Farmland Access

In 2007, to explore and address the concerns of farmland access, succession, tenure, and stewardship (FarmLASTS), a national multi-year project was initiated by a collaboration between Land for Good and the University of Vermont. According to the report compiled by FarmLASTS, only 3% of farmland buyers are new farmers. Socially disadvantaged farmers face additional challenges, including cultural and language barriers.

How will the decrease in beginning farmers affect the country? Based on policies, programs, and statements various policy makers have revealed they believe it matters to the country’s long-term food security. Some policy makers have even expressed the hope that beginning farmers will play a role in revitalizing rural communities, halting the long-term population losses the United States is suffering in those rural areas.

However, until we come up with some kind of incentive to encourage the older generation of farmers to work with beginning farmers─to ensure the stewardship of existing farmlands─the current trend is likely to continue.

Certainly it can be a harrowing experience for non-farmer landowners to sell to farmers because of the difference in the cost of farmland verses it’s value for potential development. Not all landowners are in a position to sell their property for anything less than top dollar, yet those who can afford to want to do just that.

Consumers are waking up to the health risks associated with processed foods. They’re realizing the environmental impacts of an industrialized farming system. People are turning to local foods, and farmers’ markets are on the rise across the US. In 1994 there were 1,755 farmers’ markets throughout the States; in 2014 that number had risen to 8,268─an increase of 471% over a 20-year time span.

The growth of local foods offers opportunity for beginning farmers, with farmers’ markets serving as an incubator for new farmers. Local farmers’ markets allow beginning farmers to grow their business and become a part of their community.

Until we come up with some kind of incentive to encourage the older generation of farmers to work with beginning farmers─to ensure the stewardship of existing farmlands─the current trend is likely to continue.

Agriculture Needs Community

The fact remains that fewer beginning farmers are coming into the industry, and not all of them will endure the long hard struggle to farm ownership. Innovative programs such as the Maine Farmland Trust’s “Forever Farms” project, which uses agricultural easements to preserve fertile land for farming, can help to stem the tide of farmland lost.

Unfortunately, it’s going to take more than a few organizations to rebuild and maintain a farming industry in rural America. Agriculture needs the support of it’s community. Not only is this industry dependent upon consumer support and the participation of local townsfolk, it thrives on it—and in return, feeds our country in more ways than one.

The number of beginning farmers entering agriculture is directly related to the cost of farmland and the obstacles new farmers face. At this time there are many questions left unanswered. Until policy is made to bridge the gap─to encourage more people to sell their lands as farmland and to increase access to financing─beginning farmers will continue to struggle.

For my part, I will persist in sharing my story and experiences in hopes that it will help other wanna-be farmers. With that goal in mind, I’ve recently published my first full-length book: How to Buy a Farm With NO Money. It can be done—if you want it bad enough!

YOU can support local agriculture just by sharing this article to spread the word! If you know an up-and-coming farmer—by all means—share my book with them! Share the Runamuk farm-blog! You could directly impact farming where you live, just by sharing this information with a new or beginning farmer.

Sending love and light to you and yours.

Your friendly neighborhood farmer,

Sam

Thank you for following along with the story of this lady-farmer! It is truly a privilege to live this life serving my family and community, and protecting wildlife through agricultural conservation. Check back soon for more updates from the farm, and be sure to follow @RunamukAcres on Instagram or Facebook!

Using the Oxford GDP deflator, obtainable from the November, 2023 edition of the Farm Income and Wealth Statistics.

Co-operation of farmers selling their produce is one good way to keeping food prices down and organic farming trend I hope continues to reduce the processed food of huge corporations that only care about making a profit for investors . Less fertile land and loss of land to manufacturers is another problem. Quality control of water is issue. Woes of farming.

Well, you are going to need a government which is not beholden to the property developers, in fact, does not consist of people who own property portfolios.

This rules out the Democrats and the Republicans.

I don’t know the first thing about the American Green Party, but if you want to stop the corporate lockout of the food industry, then neither of the other two will help.